A MIGHTY HEART

February 23, 2021 2022-06-02 13:25A MIGHTY HEART

This book has been translated in 16 diferent languages: English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Dutch, Spanish, Japanese, Polish, Danish, Hebrew, Chinese, Czech, Indonesian, Vietnamese & Romanian.

“Both a love story and a taut, well-paced, well-researched thriller set against the backdrop of international terrorism … Mariane Pearl is both sharp-eyed and practical.”

Houston Chronicle

“A most remarkable woman. The book is heart-wrenching and extraordinary.”

John LeCarré

“A Mighty Heart sears the soul: … Mariane Pearl’s portraits of the men and women who kept her whole … mix affection, respect, and crisp detail … [and] break your heart.”

The Philadelphia Inquirer

“A beautiful book … for its grace and compassion, for its sharp, unmitigated sense of morality and anger.”

Minneapolis Star Tribune

“Pearl’s book is a sort of mourning, a way of uniting language and memory …. [A] story of a shared life, a true love, and a true loss.”

Chicago Tribune

“A Mighty Heart is filled with tenderness and terror. Beautifully written and achingly emotional, [the Pearls’] love story is one you won’t forget.”

Lifetime

“A Mighty Heart is spare but eloquent.”

The Sunday Oregonian

“A brave and beautifully written book … Mariane Pearl moves beyond horror and grief to write elegantly and knowledgeably about the vortex of religion, politics, and terrorism into which her husband was swept.”

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“A wise, humane, and emotionally honestbook … Worldly wise but not jaded, Mariane’s singularly frank voice carries the story.”

The Washington Post

“This is a woman who has turned the horror of her loss into a commitment to honor the two principles by which Danny Pearl lived is life-ethics and truth … Her spirit is indomitable.”

The Oprah Magazine

“Mariane shared [her husband’s] philosophy of bridging cultures through words and stories, so she’s the perfect person to pen a book that elucidates his life … She had the good fortune to know [Daniel Pearl] intimately. Now so do-we.”

San Francisco Chronicle

“Pearl’s generosity and calm strength raise her book from a simple widow’s narrative into something larger: not just a personal triumph over a great personal tragedy, but a lesson in not giving up the attempt to understand.”

The New York Review of Books

I write this book for you, Danny, because you had the courage of this most solitary act: to die with your hands in chains but your heart undefeated.

I write this book to do justice to you, and to tell the truth.

I write this book to show that you were right: The task of changing a hate-filled world belongs to each one of us.

I write this book because, in suppressing your life, the terrorists tried to kill me, too, and to kill our son, Adam. They sought to kill all those who identified with you.

I write this book to defy them, and in the knowledge that your courage and spirit can inspire others.

I write this book to pay tribute to all the people who helped and supported our family through terrible times, creating an emotional bridge for us to stand on.

I write this book for you, Adam, so you know that your father was not a hero but an ordinary man. An ordinary hero with a mighty heart. I write this book for you so you can be free.

JANUARY 23, 2002. FOUR A.M.

Dawn will rise soon over Karachi. Curled in Danny’s warm embrace, I feel safe. I like that this position is called “spooning” in English. We are like spoons in a drawer, pressed to each another, each fitted to the other’s shape. I love these sweet moments of oblivion and the peace they bring me. No matter where we are — Croatia, Beirut, Bombay — this is my shelter. This is our way of meeting the challenge, of confronting the chaos of the world.

As I awaken, I struggle for the right words to describe this place. It is the curse of all journalists, I suppose, to be writing a story even as you are living it. I am not sure I’ll ever get to know Karachi. I have distrusted this city from the start, though we are partly here to find out if its bad reputation is deserved. Once relatively stable, even sleepy, Karachi became a nexus for drug and arms trafficking in the 1980s. Now the city is an intricate puzzle, decadent and beastly at the same time, metastasizing into a capital of blind hatred and violent militancy.

The Pakistani people are equally fractured. Those born in their own land hate the Muslim immigrants who arrived from India after the two countries were partitioned in 1947. The Sunni Muslims loathe the Shiite Muslims. Since 1998 more than seventy doctors have been assassinated in Karachi; most were Shiites mowed down by Sunni zealots. And the pro-Taliban fundamentalists, who have been sinking deep roots here, detest the rest of the world.

There are so many people in this city, but no one seems to know how to count them all. Are there ten million? Twelve? Fourteen? Most of Pakistan is landlocked, pressed between India and Afghanistan, with parts of its borders touching southwestern Iran and the farthermost reaches of China. But Karachi, on the brown coast of the Arabian Sea, is the country’s major port and, as such, is a magnet for migrants who drift in from the Pakistani countryside and across the border from even poorer places — Afghan villages, Bangladesh, the rural outposts of India. By day you see the poor burn under the scorching sun, selling vegetables and newspapers at dusty crossroads. At night they disappear in the labyrinthine streets, lending the city an air of foreboding. To us, this third-world city may glow with a feeble light, but Karachi draws the desperately poor like a torch draws fireflies.

Very rarely am I awake when Danny is still asleep, especially since I became pregnant. A ray of soft light enters our room, and falling back into sweet torpor, I gradually give up on the mysteries of Karachi and rejoin my husband in this privileged warm space of ours. Together, we can hold on to this night a little longer.

SEVEN A.M.

Danny is pushing back the bedroom door with his foot. He brings coffee and dry — if not stale — biscuits to stave off the fits of nausea I still fight in the morning. Sometimes I have to rush to the bathroom to retch as soon as I wake. The noise alone can turn Danny pale. He seems so unhappy to witness my suffering that I try to muffle the sound track. Danny pretends the pregnancy is making me moody. A few days ago I chanced on a less than discreet email he sent his childhood friend Danny Gill in California:

Hey!…Mariane’s belly is getting very pronounced. It’s quite a thing to see. Due date is May, ground zero is Paris. She’s sick often, moody occasionally, hungry earlier than usual, impatient but only with Pakistanis, horny when other symptoms don’t get in the way….

To my mind, Danny’s moods have become unpredictable, too. I can’t tell if it is because he is about to become a father, or because the world has gone amok in the four months since the World Trade Center was brought down, taking with it more than a few certainties. Danny is the South Asia bureau chief for The Wall Street Journal. Militant Islamic terrorism may hit anywhere on the globe, but the heart (if you can call it that) of its network is here, in this region, and the work at hand is daunting.

Danny and I have always reported alongside each other. I accompany him on most of his interviews; he comes along for most of mine. Yet I do not kid myself. He is the more experienced journalist, and he works for one of the most powerful news organizations in the world, whereas I work primarily for French public radio and television, which has barely enough money to pay for my métro tickets back home in Paris. But our differences in background and in culture make us well matched. We know naturally when to hold back and let the other speak.

I make Danny laugh to help him forget his worries; I make sure there is silence when he concentrates. And we engage each other in endless philosophical debates — about truth and courage, about how to fight preconceived ideas, about how to learn from and respect other cultures. Still, to try to shed light on the nature of terrorist activities is to plunge into a kingdom of darkness.

Already it is getting hot. To make me feel better, Danny reminds me that today is the last day of this assignment in Pakistan. Tomorrow we will check in to a five-star hotel in Dubai and stretch out on the beaches of the Arabian Gulf. It’s a roundabout way back to our home in Bombay, but Pakistan and India are now at loggerheads, and there is no longer a direct connection between the neighboring countries. Battling over the disputed Himalayan territory of Kashmir, the two nations have escalated their historical animosity to the point that the world is braced for either side to unleash an attack against the other. Both Pakistan and India have used Kashmir as an excuse to justify recent military buildups; both possess arms of mass destruction; both strike poses as if they’ll use the weapons. I think of the cops of Karachi, patrolling the streets in their pitiful uniforms, batons their only weapons.

The tension is palpable. We hear it in the voices of our Pakistani friends. On December 24 , 2001 — the rare occasion that Christmas, Hanukkah, and Eid-ul-Fitr, the end of Ramadan, coincided — Danny received a note from an anxious friend in Peshawar, a relatively unstable city on the Pakistani-Afghan border:

Happy Eid and happy Crismiss to you. Please also tell us about your wife. Are Indian armies ready to fight with us but they do not know that the Muslims will sacrifice their lives for Islam. In the case of war, India will be divided in lot of pieces and Muslim will take away his [clothes].

My prayer is that OH GOD Save my country from his enemies.

Business conditions in Pakistan especially in Peshawar are not so good….So at the end I say that God may live long for us and whole of yours family.

With best wishes,

Wasim

Wasim is the director of a noodle factory. Danny met him two years ago in the Tehran airport. A very conservative Muslim, Wasim distrusts Westerners in general, but we went to visit him last December, and he treated us as his special guests, plying us with local delights, grilled meats and pastries, and inviting us to visit the marketplaces during Ramadan. Strolling through one store, he randomly picked up a pair of high-heeled shoes, shoes no proper Muslim wife would ever wear, and he insisted on buying them for me. On another night we had the honor of being invited to dinner at his house, a two-story mansion in an overcrowded area of the city. After we arrived, Danny disappeared in a cloud of several men, while seven women swooped in to take charge of me. Sitting cross-legged on carpets and removing their veils, they studied me with intense and unapologetic curiosity as they made me eat three plates of meatballs and rice.

Danny wrote back to Wasim:

Wishing you a happy Christmas, Hanukkah, and Eid. Mariane and I are taking my colleague and our local Kashmiri carpet dealers out for Christmas dinner. So we’ll have three Muslims, two Jews and a Buddhist, which sounds like the beginning of an airplane joke, but may be a good way to wish peace on earth — or at least in Kashmir. Danny.

We are staying with Danny’s dear friend and colleague from The Wall Street Journal, Asra Q. Nomani, a most unconventional woman. An Indian-born Muslim, Asra was raised in West Virginia, and she is in Karachi to complete research on a book she’s writing about Tantra. Tantra is generally associated with the sexual practices taught in The Kama Sutra; Asra insists she is focusing on its spiritual side. She is short and feminine but athletic, and striking-looking. Hers is an assertive beauty: Her shoulder-length black hair glistens with the oil that Indians use for daily head massages, and her face is dominated by sharp, broad cheekbones and eyes so dark and large that in repose, she can look like an ancient statue of Saraswati, the goddess who possesses all the learnings of the Vedas, from wisdom to devotion. But in this world she is also outrageously avant-garde. Unmarried women do not, as a rule, live alone in Karachi, but that hasn’t stopped Asra, and she has rented a huge house in a district that is, oddly, named Defense Phase 5. Not only that, she has recently fallen in love with one of the sons of Pakistan’s elite, nine years her junior. He is an attractive young man whom I immediately find somewhat empty.

To welcome us, Asra has planted flowers at the entrance to the house, which is in a gated community, one of the most luxurious in Karachi. Here, the houses are guarded by a handful of skinny men, who take turns stationing themselves in a guardhouse, the main purpose of which is to protect them from the relentless heat. The neighbors hold good positions in the army and the government, or perhaps organized crime. The terrible gangster Dawood Ibrahim, by reputation a bloody barbarian, is supposed to have property around here. Danny has toyed with the idea of profiling him for the paper.

Inside, Asra has prepared a true honeymooners’ bedroom for us. There are flowers and pine-scented candles, a bottle of massage oil, another of bubble bath. To the left of our bed, a small window covered with wire looks out onto a room off the courtyard where a foldout cot occupies the place of honor next to a clothesline draped with children’s clothes. This is the property of the house servants, Shabir and Nasrin, who could themselves be called the property of the house, because Asra hired them when she rented the place. I visited their room. They have nothing. They sleep on the floor, and their tiny daughter, Kashva, a doll-like girl with short hair, sleeps tucked between her parents. Nasrin is pregnant. I dare not say “like me,” so different will our two children’s destinies be.

Danny draws the curtain on the scene, his gesture a perfect metaphor for how one tends to deal with poverty everywhere. Our honeymoon room already looks like a whirlwind swept through it. This is Danny’s way of moving in, his trademark. He opens his suitcases and scatters everything within them. Socks. The French comic books he uses to learn my native language (and which he thoroughly enjoys). Shaving equipment. His Flatiron mandolin, handmade in Bozeman, Montana, and more portable than his violin. Upstairs, his tools of the trade have already devoured Asra’s office — a laptop, a Palm Pilot with the special keyboard Danny uses when he’s traveling, a variety of wired devices, a digital camera, stacks of expense receipts, and Super Conquérant notebooks, which he buys in bulk in papeteries in Paris.

Danny emerges from the bathroom in his shorts, cell phone in hand. He is one of those rare men whose eyes, those chestnut green eyes, always betray him; he cannot hide anything, especially when he’s in a playful mood. I smile because I find him beautiful, and because my love for him is absolute. Without dropping the phone, he slips under the sheet. He crawls carefully over my body and reaches my rounded belly, where he starts a private conversation with our child in a tongue known only by the two of them. All I can gather is that he makes many promises for the moment the baby comes out. I weave my fingers through his thick brown hair.

Danny goes to the most unexpected hairstylists. Funny phrase, that. The more picturesque the barbershop, the happier Danny is. Most of the time the barbers don’t speak English, but this way one is always assured of a surprising result. This is Danny’s way of facing the world: with trust. When we moved to Bombay in October 2000, the first thing he did was go to the barber on our small street. The fellow might have been cutting a white boy’s hair for the first time in his entire life, but he had a great ancient barber chair with a dirty white leather seat and red armrests. I sat on the bench just behind Danny, following the action in the mirror. Everything was silent except for the drone of the flies and the snipping of the scissors. Suddenly I realized women were not supposed to be here. Well, blame it on the cultural gap, I thought; I’m staying. The barber began massaging Danny’s head so vigorously that it whipped back and forth. Danny looked stricken with shyness, and he fought hard to avoid me in the mirror. I nervously laughed so hard that tears came to my eyes. But they turned into real tears when I was startled by the awareness that we were actually going to live right here, on this very street, which was filled with rats, and where women weren’t welcome, and where everyone seemed stern and stiff and cold. Where I was going to be a foreigner. An outsider.

Danny is still talking to “Embryo,” as we call him — I think he is telling Embryo that he will be a boy. We found out the day before coming to Karachi, at a sophisticated clinic in Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital, where they not only perform prenatal sonograms but claim to be able to influence the gender of the baby.

“BOY! IT’S A BOY! WHOO HOO!! Rock n Roll!! F-in A, man! We BAD, dude, We F-ing BAD!!!” Danny emailed Danny Gill. “Don’t get me wrong, a girl would be great too. But IT’S A BOY! HOWOOOO! HOWOOOOO! BOYS RULE!!!”

I actually feel a little strange about carrying the male sex inside of me. When I tell Danny this, his eyes light up, as they always do when he’s about to crack a joke. “You know, honey,” he says, “that’s how it all started…”

This morning Danny is more solemn. “It’s incredible how much you can love somebody you haven’t even met yet,” he marvels. He says he wants to study the whole Encyclopaedia Britannica to be able to answers those questions kids never stop asking, like “How can you keep the sky from falling?”

Danny gets up and finishes dressing. His glasses give him a serious look, and when he works, he always dresses with understated elegance. He might have a little weakness for beautiful ties, but he doesn’t look anything like a baroudeur, one of those swashbuckling journalists in their ready-for-action safari jackets.

I have a cold. It is already 95 degrees, but I have a cold and a headache, and there will be a dinner party here tonight, and I don’t feel up to doing much of anything. It will take all my energy to prepare for the interview I have to tape for French radio with the director of an organization that tries to protect women from domestic violence. As in India, where the horrifying problem has received more attention, domestic abuse is rife here, with shocking numbers of wives being beaten by their husbands, or worse — attacked with acid, even burned alive.

Danny’s schedule today is especially hectic, with meetings stacked up like planes over a crowded airport. It is always this way on the final day of an assignment; there are so many more interviews to conduct, so many more leads to pursue. Among other appointments, he’s meeting with a cyber-crime expert, someone at the U.S. consulate, and a representative of the Pakistani Federal Investigation Agency (FIA). He has meetings with the Civil Aviation Authority director to talk about border surveillance as Pakistan tries to prevent terrorists from turning Karachi into their safe haven. Most pressing of all, he is investigating links between Richard C. Reid, the pitifully ugly “shoe bomber,” and a radical Muslim cleric in Karachi.

Since Reid was thwarted in his attempt to blow up a Paris-to-Miami flight on December 22, several facts have been established, in particular this: Reid was acting on orders from someone within the Al Qaeda network in Pakistan, and very possibly in this city. Originally, Reid was to fly on December 21, but he was questioned so extensively at the Paris airport, his plane left without him. He then emailed someone in Pakistan and asked, “I missed my plane, what should I do?”

The anonymous reply: “Try to take another one as soon as possible.”

Who was the man in Pakistan? The Boston Globe reported that Reid had visited the Karachi home of Sheikh Mubarak Ali Shah Gilani, an apparently respected spiritual leader. But was Gilani more than a spiritual adviser to Reid? Was it he who ordered Reid onto the Paris-to-Miami flight? After weeks of trying to track down Gilani through intermediaries, Danny finally seems to have secured an interview with him. They are to meet early this evening.

Danny will be accompanied on his morning round of appointments by a new “fixer,” a man named Saeed. The fixer is the lifeblood of the correspondent. In regions where everything from government speeches to body language must be deciphered, they serve as multidimensional translators. Navigators, too. Saeed is not getting off to a good start. He’s just called to say that he’s lost. This worries Asra. “What kind of fixer is that, who doesn’t even know his way around Karachi?” Saeed is a reporter at Jang, the major Urdu newspaper. The paper claims about two million readers, which, as Danny notes, is about as many copies as The Wall Street Journal sells; comparisons stop there, though. Saeed finally arrives an hour or so late. What is most impressive about him, besides his Western-style checked shirt and pleated trousers, is how jittery he is.

Once Danny leaves, our big house falls into silence. Across the street, parrots of a startling green color talk away, offering a welcome change from the cynical chuckling of the hooded black crows that provide unavoidable company in southern Asia. In the main room, Nasrin crouches on the floor, gathering dust with a handmade broom of twigs tied up with rope. Her daughter, Kashva, follows her like a little shadow. I scare the girl in spite of my attempts to befriend her, but she is fascinated by Danny, who is always more attractive to children than I am.

My headache is frightening. I think with nostalgia about the days when aspirin was permissible. I return to our room to rest a bit, and to daydream about Danny, who is out reporting in the city. I love the way the shirt he so carefully irons in the morning invariably winds up rumpled and falling out of his trousers by early afternoon. Danny erupts into people’s offices, his hands always too full, juggling Palm Pilot and pads and pens and documents spilling out of manila envelopes. He wins people over so naturally. I think it is a subtle combination of his boyishness and good manners. Or is it because Danny never lies?

In his early days at the Journal, Danny became known for his delightful A-heds, the quirky articles the paper runs in the middle of the front page. He wrote about the world’s biggest carpet being woven in Iran (“This is a small town in search of a really big floor”). In Astrakhan he wrote about caviar merchants who are increasing the caviar supply by injecting sturgeons with hormones to make them produce more eggs, which can then be scooped out during a sort of fish cesarean section (“Thus was stitch-free sturgeon surgery born”). Danny can spin unexpected tales straight out of the ordinary.

But I really admire the way Danny has begun to go deeper, further, with his reporting in recent years. The territory he now explores is less certain. He weaves his way through a world filled with narrow, conflicting views. He peers down alleyways, connects the dots, explains the butterfly effect — how the slightest movement in one place can have massive consequences somewhere else. I see Danny growing and taking responsibility as a writer and as a man. He is becoming more genuinely concerned about a world he embraces ambitiously. He makes me believe in the power of journalism.

A year ago in Bombay, influenced by the spiritual heft of India, I rolled my office chair next to Danny’s desk and asked him which value he considered most essential — in other words, what did he see as his personal religion? I didn’t mean a religion inherited from a tradition, but the values he placed above all else. Danny, who was then working on an article about pharmaceutical products, told me he understood and promised he would think it over. A few minutes later, he rolled his matching chair next to mine. “Ethics,” he declared with a triumphant air. “Ethics and truth.”

In a few days, that conviction was put to the test when we arrived in the state of Gujarat in northern India. The region had suffered a massive earthquake, and casualties were considerable. Neither of us had ever reported a natural disaster, and as we came closer to the epicenter, the horror almost overwhelmed us. The earth’s crust seemed to have crumbled under the force; it was easy to see that hundreds of victims were buried in the rubble. We watched mutely as a corpse was extracted. The smell of death was everywhere.

I was working as part of a reporting team for a French publication. When I kicked in my file, one of the staff writers didn’t find my descriptions “colorful enough” and proceeded to invent a series of scintillating details. Back in Bombay, Danny and I had dinner with him. The man was a senior reporter, but all he could talk about was the contempt with which he viewed journalism. He talked about illusions and lies, about news as spectacle. He seemed totally indifferent to any sense of responsibility, to any regard for truth. He seemed half dead.

After the meal, Danny slipped away to his desk, where, depressed, he sat for a long time with his head in his hands. He had already written an article about the economic consequences of the earthquake, but he hadn’t been able to shake either the stench of decomposing bodies or the feeling that he’d failed to adequately, truthfully describe what he’d witnessed. So he wrote a follow-up:

What is India’s earthquake zone really like? It smells. It reeks. You can’t imagine the odor of several hundred bodies, decaying for five days as search teams pick away at slabs of crumbled buildings in this town….Numbers of dead are thrown about — 25,000, 100,000 — but nobody really knows. And it isn’t just the number that explains why the world media are here. AIDS will kill more Indians this year but get less coverage here. In India’s Orissa state, reports are emerging of starvation from drought. In Afghanistan, refugees are freezing to death in camps. But an earthquake is sudden death, a much more compelling story…

Lying on our bed in Asra’s unlikely house, waiting for my headache to subside, I flip desultorily through a notebook I started writing three weeks ago, when we were last here. We celebrated New Year’s Eve with Asra and her young lover, who took us to countless parties of very little interest, where everyone was dressed in black, as in New York or Bombay. In the car, between destinations, I took notes (the irregularity of my handwriting evidence of The Lover’s increasingly high spirits):

Karachi, December 31st, 2001, 22:45. Three journalists about to spend New Years in Karachi. All three in love. Happy….Tense about what’s about to happen in 2002? Not a single word spoken indicating worries. If bin Laden’s name is mentioned, it is for jokes only.

I arrived from Paris this morning. I went half way across the globe to be together with my loving husband and my coming baby. I brought some cheese from my fine food store in Montmartre and some scotch for Danny in a little bottle.

This guy is driving like a nut…

Danny is back before four P.M. for a brief visit. As usual, I run into his arms and bury my face in his neck. I stay there, wanting to get drunk on his smell, wanting to feel some of his sweat. I do not like to be separated from him. Sometimes, after I’ve gone somewhere, I find him at the front door waiting for my return. He takes me in his arms and tells me how much he has missed me. He squeezes me tight with one hand, and with the other, he caresses my face, calling me “My wife, my life.”

Occasionally I like to be separated from him for a few days just to savor this feeling we have — painful but delicious — when the one we love is absent. Just for the pleasure of finding him again when he comes to pick me up at the airport. Of reading the emails he sends me from a stop in transit, for the mere pleasure of hearing him tell me, “I’m on my way.” Only when I am back with him do I feel whole.

Conventionally speaking, I am not a good spouse. I can’t sew or iron. I can cook only one dish, and I never remember to buy toilet paper. The good news is that Danny doesn’t seem to notice (except for the toilet paper). Our complicity grows richer every day, made out of trying moments, new challenges, true joys. Danny loves to be proud of me. Last October, at a film festival in Montreal, I won an award for a controversial documentary I made for French and German public television about Israel’s use of genetic screening. Under Israel’s Law of Return, almost any Jew has the right to return to the ancient homeland. But how do you make sure someone is actually Jewish? To determine who qualifies, Israeli authorities have used DNA testing to examine applicants’ genetic makeup. My film explored the political and sociological implications of this process, which are confusing and disturbing. The moment he heard the news, Danny, who was in Kuwait, shot me an email: “My Baby’s an award-winner! signed, Proud Husband.”

It is time for all of us to get moving. I’m running late for my interview with the domestic-violence expert; Asra has errands to run before the dinner party; Danny must get over to the headquarters of Cybernet, an internet service provider, to see what information he can gather on Richard C. Reid’s email exchange. Then he will move on to two more appointments before, at last, his rendezvous with the elusive Sheikh Gilani. We scurry through the house, tossing our tools into our bags — tape recorders, cell phones, special notepads, Palms. How is it that in a house this big you can still get in one another’s way?

Asra calls over to the Sheraton Hotel to line up a car for each of us. In Karachi you don’t fool around. Conventional protocol decrees that you hire a trustworthy car and driver to take you on your rounds and wait at each stop. Although he has traveled all over the world and reported from some of its more dangerous corners, Danny is a believer in playing it safe. He is by nature a cautious man. When we moved to Bombay, he drove our car dealer crazy by insisting that seat belts be installed in the backseat of our gray Hyundai Santro. In the backseat? They thought it was cute; he felt it was imperative.

The Sheraton has no car to send over. This has never happened before. Asra tries another local service that rents out cars and drivers, but there, too, the wait will be long — at least twenty minutes. If we wait that long, Danny will miss his first appointment, which will derail his second appointment and threaten the third. In desperation, we send Shabir, the house servant, out past the guardhouse to hail two cabs at the corner. As if it will make one come faster, Danny impatiently stands on his toes and hops up and down. He repeatedly checks the fancy silver watch I gave him for his last birthday, his thirty-eighth. At last Shabir reappears on his bicycle, leading two taxis. I signal to Danny to take the first, since he is in the greater hurry. After he tosses his bag in, he cups my neck with his free hand, pulls me to him, and kisses my cheek. Then he dives into the backseat of the cab.

In a matter of seconds, Danny is gone.

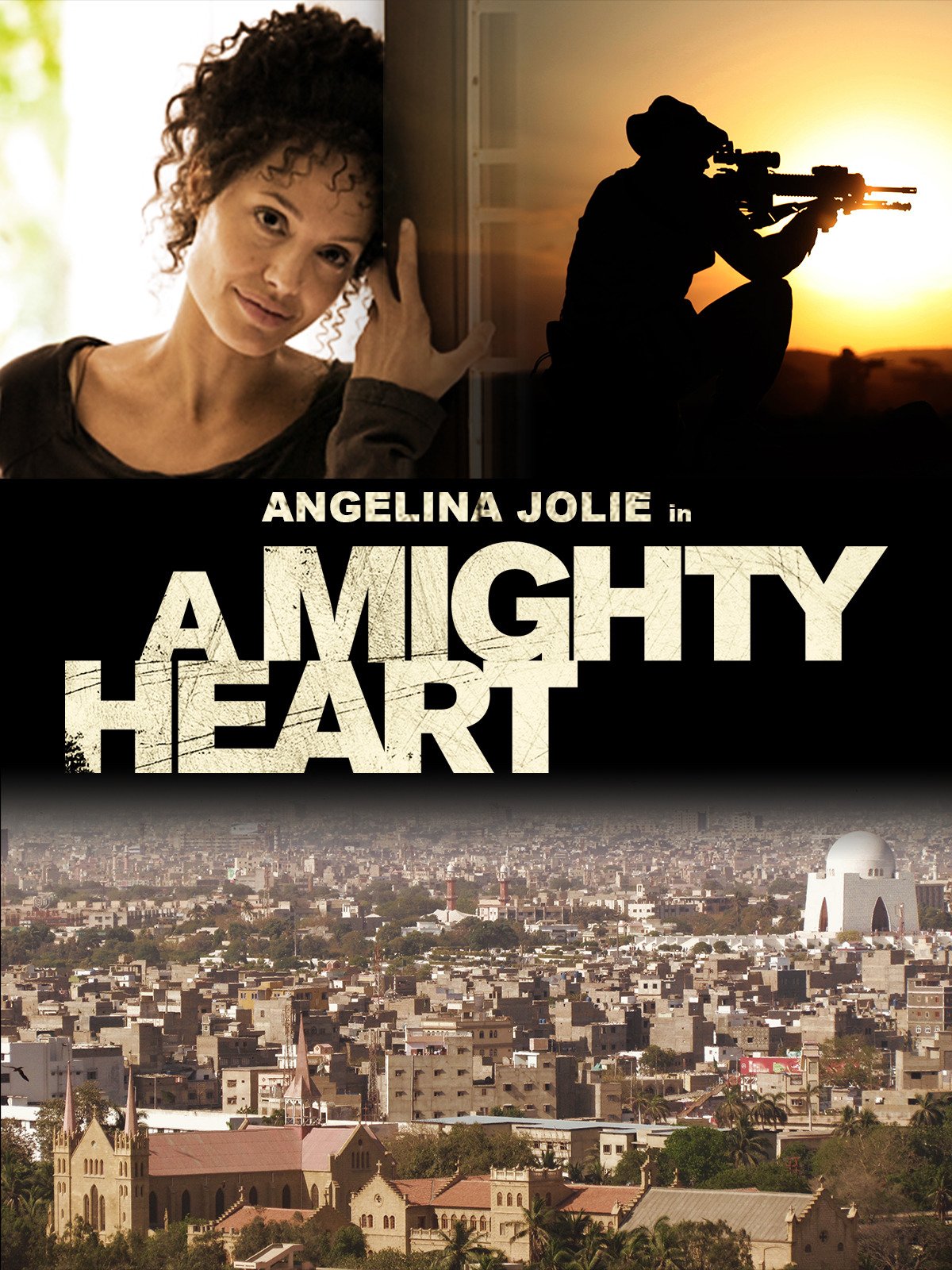

A Mighty Heart was adapted as a dramatic 2007 film of the same name, starring Angelina Jolie as Mariane Pearl, Dan Futterman as Daniel Pearl, and Archie Panjabi as their friend and colleague Asra Nomani.

The movie also covers efforts by the US Department of Justice, the U.S. Department of State’s Diplomatic Security Service (DSS), and the Central Intelligence of Pakistan to track the kidnappers and bring them to justice.