IN SEARCH OF HOPE

February 23, 2021 2024-05-13 19:25IN SEARCH OF HOPE

In Search of Hope

“So I embarked on this journey in search of light. It couldn’t be a divine light—it had to be human, as I believe only people can undo what people have created."

“I embarked on a journey around the world—a physical trip with a spiritual motivation. It had to do with the meaning of my life and the meaning of the deaths of those I have loved…” But first and foremost, it had to do with my son. How could I inspire my boy, Adam now five years old, to embrace the world and claim it as his own? It would be legitimate for him to be scared; aren’t we all? But was there a way he could genuinely feel hopeful instead?

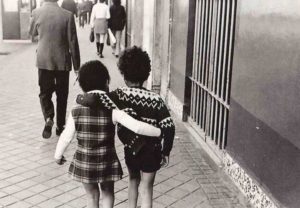

one stop on Mariane’s journey.

When confronted with seemingly endless headlines about everything that’s going on in the world, most of us take it all in on automatic pilot, struggling to resist the claws of helplessness—that feeling that makes the heart crack open the same way droughts split the thirsty earth. Those cracks in our hearts are where fear settles, distorting our perception of the world and our relationships with others. That fear allows the values that are essential to our integrity—justice and dignity, empathy and compassion—to remain hostage to empty rhetoric. But that’s not the world. Not necessarily. And the women in this book will prove it.

Personally, I learned the lesson about helplessness the hard way, when my father killed himself. A Dutch idealist, he believed politics could save the world, and so he enthusiastically joined other people’s revolutions in Africa, Portugal, Cuba and France. My dad did not take into account that people are people; some thirst for power, others are easily lured into corruption. When politics failed him, disillusion hit him hard. I was nine years old when he passed away. The Cuban revolution had turned into a dictatorship; the French students’ rebellion of May 1968 was long forgotten. Africa was soaking into its own blood; and my father was dead. But his last words to me saved my life. It was the conclusion he had reached after a lifetime of searching for the meaning of his own life in the midst of demonstrations and feverish political plans. These words are my heritage, and no money could buy their wisdom: “Don’t be cynical,” my father told me. “Cynicism is the weapon of the weak.”

Then there was my Cuban mother, who taught me how to live. She believed in people, ordinary ones. She had many friends and was expert in matters of the heart. She practically raised all the kids on the Paris block where I grew up, and she had genuine faith in them. Even though she was a woman left alone with two children far away from her beloved native Cuba, she wasn’t helpless. To us children she was a triumphant queen, blessed with the fit of bringing others joy. She passed away in 1999.

A few years later, my husband, Danny Pearl, a reporter for The Wall Street Journal, was kidnapped and brutally murdered by religious extremists in Pakistan. I was five months pregnant with our son. Danny’s killers claimed that he was a spy working for the CIA and Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency, and that because he was a Jew and an American, he deserved death. In reality, Danny was a true citizen of the world who spoke several languages, even some Arabic; he was full of life, smart as hell and funny, too. I adored him. When he died, everything I learned from my parents’ lives and deaths came back to me—the politics, the cynicism, my mother’s fundamental belief in human nature, the thirst for justice, the sense of pride, the quest for dignity. It all came back. And I knew too well the one thing that could defeat me and, my extension, my husband’s memory and our son: helplessness. I decided that if those who killed my husband were determined to show the gruesome side of humanity, I would display its integrity, beauty and resilience. That would be my true revenge.

So I embarked on this journey in search of light. It couldn’t be a divine light—it had to be human, as I believe only people can undo what people have created. And I chose to focus on women. Why women? With all due respect to the other half of humanity, I have found that women are the most courageous, tough and determined agents of change around—that’s just the way it is on every continent. If women were in power everywhere, I believe that the world would be in different shape. Women are the foundation of every family—and every community—and so when a woman stands up to fight for her beliefs, she lifts up communities when she raises her fist. Because the women profiled in this book knew to fight helplessness first, no evil person or deed has been able to stop them. It doesn’t matter what others did wrong or how little power they once thought they possessed. They fought doubts and fears, converted anger into indignation and indignation into action, and in doing so gave birth to a renewed hope. Any woman or man who builds hope never fails to inspire it in others.

The women featured here have championed issues that ultimately affect us all. They are real women who have cried, sweat and bled, each making her own life the raw material from which a role model has arisen. With them, I marched into the brothers of Phnom Penh, where I looked into the eyes of five-year-olds who had been raped and couldn’t even blink anymore, their little faces frozen in terror. I saw them find their smiles in the arms of Somaly Mam, the woman who saved them. I saw entire families in Uganda defeated by AIDS, all staring at the ground, as if wanting to be swallowed by it. But there was Dr. Julian Atim, the young doctor who herself lost both parents to the disease, teaching other AIDS orphans that they, too, could become physicians and save lives. I saw housewives in Havana whose husbands were rotting in jail simply because they believe freedom isn’t a negotiable right; these women led dignified protests, resisting the fear that has quieted Cuba for almost 50 years. I met Lydia Cacho, the Mexican journalist who has risked her life to unveil a pedophile network involving politicians and businessman, and Mayerly Sanchez, who at 23 is leading a group of Columbian children seeking to halt years of violence in their country. There are other women featured here—and still others I haven’t met who I hope will soon join this informal international network of women with faith and guts.

I embarked on this journey with the help of Glamour magazine, which has supported my quest and trusted my work. For inspiration along the way, I have turned time and time again to a quote from a speech the late Senator Robert Kennedy gave at the University of Cape Town, in South Africa, in 1966:

“Few will have the greatness to bend history; but each of us can work to change a small portion of events, and in the total of all those acts will be written the history of this generation…It is from numberless diverse acts of courage and belief that human history is thus shaped. Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.”

Here are some ripples of hope: stories of human antidote.

MARCHING FOR FREEDOM

The Ladies in White · Cuba · June 2006

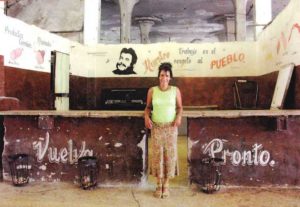

On a bright Sunday morning in Havana, I watched as more than a dozen women dressed in white, each carrying a pink gladiolus, marched along Fifth Avenue, an elegant street lined with neatly trimmed shrubbery and mansions painted in faded pastels. It was a highly unusual occurrence in communist Cuba: a political protest, albeit a quiet one. There were no slogans to be heard, no signs to be read. The women said nothing, but their silence contained a significant cry for freedom.

They are known as the Ladies in White—the wives, mothers, sisters and daughters of 75 political prisoners jailed in 2003 by Fidel Castro. The women were demanding the release of these men from prison. You could say they were staring down a dictator.

I visited Cuba in June—on the second stop in my journey around the world for Glamour—just weeks before Castro fell ill and threw the future of his regime into doubt. The protest I witnessed offered a poignant snapshot of a Cuba closing in on a half-century of life under communist rule. Ever since Castro came to power in the fifties, Cubans had grown used to waiting for things—waiting in line to collect rationed food, waiting to be reunited with loved ones who fled an oppressive regime, waiting for the embargo imposed by the United States to end. Waiting for history to turn this seemingly endless page and move on. In that atmosphere, the Ladies in White represent the rarest of breeds—Cubans who found a way to say, publicly: enough waiting.

The men they hoped to free were arrested for being peaceful activists for democracy and human rights, according to their relatives. Some were sentenced to up to 28 years. The government claimed the men were dissidents whose actions undermined the Cuban regime. For three years, the Ladies in White have marched on their behalf, almost every Sunday after mass at the church of Saint Rita, the Roman Catholic patron saint of lost causes. And they were still marching as of press time, despite the political uncertainty in the country. Their gatherings have come to embody the frustration of a people longing for freedom.

It felt odd yet reassuring to be back in Cuba on this trip. I have family in Havana, and I have been visiting this island since I was a child. My mother was born in Cuba, and she left in 1965. It seemed that little had changed since then. People were warm and friendly, quick to have a drink, dance and share jokes as if there were no tomorrows to worry about, or simply no change in sight under Castro’s rule.

After watching the women march, I went to meet Laura Pollan, 54, a Lady in White who is a teacher of Spanish literature, at her home. On my way, I saw Dodges and Chryslers from the sixties, their paint sun-bleached to pale blue and dusty red, and passed billboards bearing slogans like “The Nation or Death” and “Capitalists, You Don’t Scare Us.”

Laura’s home is the informal headquarters of the Ladies in White, or Damas en Blanco, as they are known in Cuba. When I arrived, she was sitting on a rocking chair in her living room, sweating profusely. Her electric fan didn’t work, and she had to rely on neighbors for water since her own plumbing was broken. Her front door was wide open to the busy street. Cars constantly blew their horns, trying to avoid young men on Chinese-made bicycles. Across the way, a band started rehearsing a song celebrating the joys of lovemaking. Children played soccer on the street corner, while women wearing tight shorts strolled by, calling out to each other.

Laura told me how her husband, Hector, a journalist, had ended up in jail. First he resigned from the Communist party—a highly symbolic gesture. Then he became involved in groups demanding freedom of speech and the right to vote. As a result, the government labeled him “ideologically unfit,” Laura said. One afternoon in 2003, she came home to find that the police had ransacked her house. “They scattered all our papers on the floors, emptied the drawers and even searched the plants,” she said. As the police led Hector away that day, he told her, “Do not be ashamed. I am not a thief. I have never hurt anyone. I am being arrested for my ideas.” The government accused him of helping terrorists plan attacks against Cuba, and he was sentenced to 20 years in jail, Laura said. “In fact,” she added, “the only weapons they ever found were paper and a typewriter from 1958.”

When Hector and the other men were arrested, in what has come to be known as “Black Spring,” their women started exchanging letters of support. Soon dozens of them began marching. However, over time, the protestors’ numbers dwindled, Laura said, amid pressure from the police, who would sometimes surround the women’s houses on Sundays and prevent them from going out.

Laura’s story was interrupted when a man holding little conical paper bags stopped by her door. “Here’s the peanut man,” he shouted in a singsong voice. “Peanuuuts!” Laura smiled and turned to me. “We might be ordinary women,” she said, “but we have unshakable beliefs.” She paused and then added, “Listen, if there should be only one Lady in White left, that will be me.”

I also met one of the younger members of the movement, Katia Martin, a 25-year-old mother of identical twin girls. As we sat in a tiny public park ringed by giant royal palm trees, she told me about her husband, Ricardo, and his ordeal in jail. “The stress is killing us both,” Katia said. “Ricardo’s health is deteriorating quickly. He has lost his voice because of a cyst on his vocal cords, and he gets no medical attention. The food in prison is terrible, and the hygiene is the worst.” Katia, like the other women, is allowed to visit her husband only twice a month. It is unclear when he will be released.

Yet despite the many hurdles for the Ladies in White, their message has been heard. In December they received a European Parliament award, the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, named after Soviet scientist and human rights activist Andrei Sakharov. The women were not allowed to travel overseas to receive the honor, but it helped keep them going.

“I am confident we will free our men eventually,” said Lidia Valdes, a 67-year-old housewife who talked with me one afternoon at her home. Her husband of 40 years, Arnaldo, an economist and writer, was sentenced to 18 years. Lidia said she feels empowered by the group’s solidarity. Through the Ladies in White, she said, “I have come to trust humanity again.”

I am moved by the women’s peaceful struggle and their colossal but quiet determination. I can’t help but think of my own late mother, a poor, proud and strong woman. I imagine her marching along with these women, holding in the frustration born of this forced silence. As for me, I don’t know if I could master such self-control and keep silent each Sunday; I would probably end up in jail. My mom was lucky she could leave Cuba when she married my dad, a Dutch man, and moved to Europe in 1965. After that, most residents weren’t allowed to travel freely. But my mother could never truly leave her beloved island behind; my childhood was colored with her descriptions of the music, the food and the culture.

She waited throughout her life for the Cuban people to enjoy freedom. I remember once, when one of the country’s periodic mass exoduses occurred, my mother sat in front of our television in Paris and sobbed for hours. Entire families fled the island on makeshift rafts, some built with house doors tied to truck wheels. We watched as our people became little dots in the ocean, fading from sight. I learned then, at 14, how easy it is to take freedom for granted, while others have to risk their lives for it.

Personally, I can’t imagine a more lonely feeling than being imprisoned for your ideals, on an island. What better metaphor for isolation? But these jailed fathers, husbands, sons and brothers, even in the darkest corners of their cells, have never been alone. They’ve taken courage from the Ladies in White, who have marched because freedom is a quest that knows no compromise. I’m always reminded when in Cuba of a favorite quote from Robert Green Ingersoll, a nineteenth-century American orator: “What light is to the eyes, what air is to the lungs, what love is to the heart, liberty is to the soul of man.”

MADAME PRESIDENT

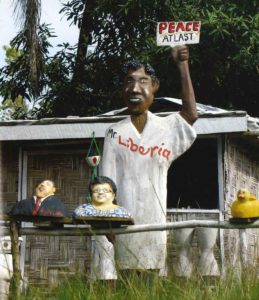

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf · Liberia · July 2006

As my plane prepares to land in the tiny West African nation of Liberia, I search for the familiar lights of a city at night, but Monrovia, the capital, is wrapped in darkness. The entire country has had almost no electricity for more than a decade—just one example of the damage done by civil war. My jetliner begins its descent, and through the windows there is nothing to see until we near the runway, which has been lit with the aid of a power generator.

I have come to Monrovia to meet Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the president of Liberia and the first woman ever to be elected head of an African country. At 68, an age when most people retire, she has taken on the daunting task of raising a country from its ashes. These are not mere words; Liberia has been stripped bare by warlords who raped, murdered and terrorized its people during 14 years of civil war. More than a million civilians either died or fled the country; even children were recruited for combat. A cease-fire was finally brokered in 2003, and in late 2005 the United Nations helped supervise a democratic election. President Johnson Sirleaf took office in January.

Liberia, which was founded by freed slaves from America in 1847, is now waking up from its nightmare, and the landscape is devastating. Eighty percent of the population is unemployed, corruption is rampant and there is no running water; only a handful of buildings even have generators. The U.N. keeps 15,000 soldiers here on a peacekeeping mission.

Monrovia is the third stop on my journey around the world for Glamour, and I have two days to explore the city before meeting the president. On the streets, people look sad and tired, and there are few opportunities to escape the grim reality—no obvious bookstores or theaters or anyplace to go after dark, except for a few beer bars lit by dim oil lamps.

In the sprawling shopping district known as the Red-Light Market, I see hundreds of vendors offering items that I struggle to identify, like red palm oil, chicken feet and live snails, but there are very few buyers. I meet a serene woman named Femata Morris, who explains why she voted for the president. “She is not interested in wars. She wants to put our children to school,” she says. Then she quickly adds, “Now you stop talking and buy me something.”

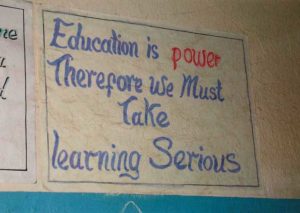

Schools in Monrovia have recently reopened after years of interruption due to war. I stop by a public school and meet the principal, Sarah Barclay. “Many of the children are depressed or hungry or both,” she says. She introduces me to two girls, Charlotte, 11, and Senebu, 12. Charlotte looks awkwardly elegant with her patchwork dress and patent-leather handbag that she holds tightly to her chest. She tells me that during the war, she would run outside to pump water as quickly as she could because she was terrified of rockets. Her classroom has been filling slowly with children who lost family members to the fighting.

The girls and I start playing a game I call “Ask the president.” They can ask any questions they want, and I will relay them to President Johnson Sirleaf. “Can I be a doctor?” asks Charlotte. “Or a scientist!” shouts Senebu. Then she adds, “Are we going to have electricity?”

Two days later, I arrive for my meeting with President Johnson Sirleaf on the fourth floor of the Liberian Presidential Palace, which is hardly palatial. The president’s offices are decorated with red carpeting and antique furniture, but the floors below it are wrecked by years of looting. Barefoot men repair walls with drills while women in brightly colored dresses clean cracked windows.

In the lobby, I see a dramatic portrait gallery of the men who have led Liberia. I can imagine the guided tour: Here is President William Tolbert, who was murdered by allies of President Samuel Doe, who was killed by supporters of President Charles Taylor, who is currently being tried for war crimes. At the end of this collection of power-hungry men is a smiling photograph of President Johnson Sirleaf, looking regal in her traditional outfit in yellow.

When I enter her office, the president has the pained look of someone who is about to sit in a dentist’s chair. I sense that she is not thrilled with the press. Ever since her election, she has answered many questions about Liberia’s woes, and early in her tenure she was criticized for her reluctance to push for the prosecution of President Taylor, her predecessor. (She had expressed concern about backlash from his supporters.) “Sick of the media?” I ask. She raises her eyebrows, sighs and gives me a slight smile. There’s something grandmotherly about her, with her round face and curly hair, but behind her gold-rimmed glasses is the determined gaze of a woman on a mission. I can see why she is called the Iron Lady here. “Why are you journalists always focusing on what is wrong?” she asks. “Why don’t you see the beauty of our continent? Why don’t you see the women who walk miles under the sun, work 14 hours a day and then go home and wash their children’s clothes so they can be clean for school the next day?”

She tells me her biggest task is “to provide dignity, hope and education to a deeply wounded youth.” This mother of four learned the importance of schooling from her own mother, a teacher. “My mom would travel by canoe to different schools to teach classes,” she says. “She knew that education was the only true road ahead.”

A graduate herself of Liberia’s schools, the president also earned a master’s from Harvard, then spent several years abroad working in finance. Between foreign jobs, she got involved in Liberian politics. In 1997 she ran against Taylor for president and lost. In the 2005 election, her opponent was George Weah, a popular soccer star; she won, she says, by appealing to the hearts of mothers with her vow to put kids back in school.

I tell her of the girls’ questions, and she lights up. “See how the ambitions have changed!” she says. A few years ago, no girl here would have dreamed of being a scientist. “It is thanks to our struggle for gender equity, the feminine revolution,” she says. She turns to her aide and adds, “This is what we need to do: Talk to the children.”

Still, as our interview draws to a close and I think about the enormous challenges she faces, I can’t help but ask, “How are you going to manage?” She shrugs. “Deeds say more than words. I am going to set an example, like shaking the hands that have hurt me. This is the only way I can free myself and inspire my country.”

Before leaving her office, I glance out the window and see two men sweeping dirt from the pavement, revealing a freshly painted Liberian flag. It seems that everywhere I look, I see a country trying to rebuild itself and move on from the past.

The next day at dusk, I hire a driver to take me to the airport. The rain is pouring, creating gigantic ponds bordered with mud and garbage. The car’s headlights reveal only the rainfall and an occasional man by the side of the road, walking bent over as if to keep his middle dry. My driver is visibly nervous. The night looks so dense, I feel as if it could swallow us both. I wish I were driving; at least then I would have a wheel to hold on to.

Finally, the airport appears like a mirage—but it seems that we haven’t made it on time. “The flight is closed,” says a laconic airport employee. Faced with the dreadful prospect of the ride back to the city with no streetlights, I grab an immigration officer and promise him a bribe to get me on the plane. I run with him onto the tarmac, holding my $50 bill tight, until a flight attendant sees me coming.

When the plane takes off, my heart is beating fast. Once again I stare out the window into the darkness below. I’m unable to take my mind off the woman I came to meet and the work before her. I remember the schoolgirl who asked if the electricity would be turned on in her city. “Yes, Senebu,” the principal had said, putting her hand on the girl’s head. “Light by light, the electricity will come back.”

JUSTICE GETS A VOICE

Lydia Cacho · Mexico · August 2006

When I first heard about Mexican journalist Lydia Cacho, I knew I wanted to meet her. This remarkable woman created an international uproar last year after she wrote a book claiming that local power brokers were tied to a pedophile ring in the popular resort town of Cancun. But she, and I, had a problem: Too many people wanted Lydia dead.

For the past two decades, this beautiful 43-year-old has given a voice to Mexico’s women, children and victims of abuse. She has written about everything from domestic violence to organized crime and political corruption. As a result, she has been jailed and threatened with rape and death. Now she travels with bodyguards almost everywhere she goes.

Clearly, if I planned to see Lydia, I had to be willing to take a risk. I considered this as I sat in my apartment in Paris one evening and watched my four-and-a-half-year-old son, Adam, play by my side. He was wearing a Superman cape on top of a Zorro outfit, and was chasing bad guys with his water gun. Adam never met his father. I was five months pregnant when my husband, Danny, a reporter for The Wall Street Journal, was murdered in Pakistan as he was investigating Islamic terrorists after 9/11.

I thought about the many journalists around the world who have been killed since Danny’s death. Iraq has been especially dangerous for reporters, but so has Mexico, where more than a dozen journalists have died in the last few years for writing about the drug trade and other criminal activities. I started to worry that reporters could become an endangered species. And so I decided to fly to Mexico.

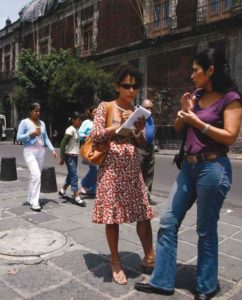

At Lydia’s suggestion, we agreed not to meet in her home base of Cancun, but in the capital, Mexico City, which was in the midst of its own ordeal during my visit in August. Following the country’s recent presidential elections, thousands of protesters had transformed the city’s main avenue into a vast camping site. People demanding a recount of the votes had come together to shout slogans, wave signs or gather signatures. Everywhere I walked, I felt men’s eyes upon me. Some of the stares were harmless, but others were lecherous, making me feel like one of those scary sex dolls with a round mouth. Such a testosterone-filled atmosphere made me appreciate why Lydia has focused her work on women.

When she and I met, Lydia struck me as incredibly composed for someone who is forced to consider that every morning might be her last. I sat by her side in the car as we inched along the busy streets of Mexico City, on our way to a quiet suburb. Lydia talked constantly on her cell phone. Each time she hung up, the phone would ring again, and she would reassure the worried people on the other end.

She began to tell me how she got her start in this business. “At first,” she said, smiling, “I wasn’t sure my writing could make a difference.” In fact, when she moved to Cancun in her early twenties, Lydia didn’t intend to change the world in any major way. “I am a melancholic at heart,” she said half-jokingly. “I pictured myself living by the sea, writing novels and painting.” But Lydia had come from a family of strong women who were feminists before the term became trendy. Her French grandmother opposed the Nazis in Europe during World War II, then married a Portuguese man and eventually moved to Mexico. Lydia’s mother, who grew up in Mexico, became an activist for women’s rights. She felt strongly that it was better to expose her children to the world than to protect them from it, and so the family lived in a poor neighborhood, even though they could afford better. Lydia’s mother used to tell her, “Once you have witnessed something, you bear a responsibility for it.”

No wonder that soon after Lydia moved to Cancun—a paradise of lush beach resorts—she began to feel a sense of unease. “This was a man-made heaven built solely to make money,” she told me. “It was a city without a heart. Nobody had bothered to think much about schools or social services or even culture.” Her journalistic instincts began to kick in, and she set out to find local residents who had been displaced by the builders. She discovered a handful of them in an impoverished community two hours from the tourist zone. “There was no running water. No food. I saw a malnourished woman whose baby had just died of hunger,” she said. She decided to write a column about it for a local newspaper. “The reaction was extraordinary,” Lydia said. Readers were so moved that they donated supplies and medicine. Thus she changed the course of her own life for good.

When Lydia and I finally made it out of the traffic jam in Mexico City, I realized that there were no bodyguards following us. “I lost them!” she said with a childlike smile, and for a moment we felt free, as if we were in one of my favorite movies, Thelma and Louise.

Later, as we walked together along the suburb’s cobblestone streets, an old man on crutches approached me. “Is that Lydia Cacho?” he asked. I nodded. “Please tell her to be careful,” he whispered. “There are evil people.”

Lydia continued to tell me her story, explaining how she made waves again early in her career by writing about the proliferation of HIV in the Cancun area. The local governor called her at 11 P.M. the night the story ran, she said. He told her, “There is no AIDS in my province.” She replied, “In yours maybe not, but in mine, yes!” The next day she appeared on a radio show and talked about the call. This very public act surprised her fellow journalists. “Even my colleagues didn’t understand me,” Lydia said. “Sadly, many Mexican journalists are easy to buy. Some of my counterparts live on bribe money, and those who won’t give in to bribes usually get killed.”

Lydia kept writing, mainly about government corruption and domestic violence, but soon the phone calls she received threatened her life.

In 1998 Lydia was brutally beaten and raped in the bathroom of a bus station. Despite suffering a concussion and broken ribs, she got herself to a hospital. Lydia does not know whether the attack was related to her work.

This experience made her even more determined to stand up for women. At the same time, Lydia decided that reporting wasn’t enough. So she raised money to build a center for battered women. “Women had no rights, and if they stood up for themselves, they could be beaten or killed,” she said. Women now come to the shelter from all walks of life: wives of drug dealers and farmers, as well as American girls who get assaulted on spring break. The center provides health care and schooling for children.

In 2004 Lydia set off the biggest firestorm of her career with her book about the pedophile ring in Cancun, Los Demonios del Eden (The Demons of Eden). She was arrested on libel charges a year later (under Mexican law, Lydia explained, reporters have to prove that they didn’t intend to damage the reputation of their subject). She said she was driven by police to a jail 20 hours from Cancun, while the officers hinted at a plan to rape her. She was released unharmed. Then, last February, the media got hold of a tape on which a businessman named in her book appeared to be plotting with a Mexican governor to have her arrested and raped. (The men dispute the legality of the tape.) Amnesty International filed protests on her behalf, and Lydia talked about it on shows such as ABC’s Nightline. “This is my strategy,” Lydia said. “Each time someone threatens me, I talk about it publicly.”

Lydia, who still faces some libel charges, said that Mexico’s Supreme Court is investigating whether her civil rights were violated during her arrest. She is continuing to work as a reporter while also teaching journalism workshops. “Reporters are not world-peace missionaries,” she said. “But by conveying people’s struggles, we create awareness, which is the first step to bringing about change.”

When I left Mexico City, I feared for Lydia’s life, but I also felt inspired by her mission. I understood her humble sense of triumph. Knowledge and responsibility bring hope, while ignorance feeds on fear. If Lydia stopped halfway, she would be like someone who sees light at the end of a tunnel but chooses to remain in the dark.

Back in Paris with Adam, I thought about what I would say to my son if he ever wanted to become a reporter. I would tell him that journalism was the cement of my relationship with his father. I so believe in the importance of this profession that I could never oppose the same ambition in my child. As we were having dinner one night, Adam asked me about my trip to Mexico. He wanted to know if I had caught any bad guys. “No,” I answered. “But wait a few years, and I’ll tell you about a woman named Lydia.”

NO LONGER INVISIBLE

Fatima Elayoubi · France · September 2006

Fatima Elayoubi’s flat in the somber Parisian suburbs is a nostalgic tribute to her native Morocco and the family she left behind more than 20 years ago. On the wall, a clock with a picture of Mecca ticks away the time. The dining table is draped with a cloth Fatima knitted herself, and in the corner of the living room there is an enormous photograph of her mother, her face wrinkled by a life spent under the North African sun. Scarcely educated, Fatima—like many Arab immigrant women—spent years in the shadows, cleaning, cooking and doing the laundry for better-off French families.

But Fatima, 54, also achieved the unimaginable for a woman of her background. Each night, after she’d finished scrubbing other people’s homes, she painstakingly scribbled away on a memoir that explored her harsh life as a stranger in a foreign land. Then she had the confidence to believe people should read it. Her book, Prière à la Lune (Prayer to the Moon), became a surprise hit—one that revealed to Parisians the lives of a population they had long ignored.

When I tell people I grew up in Paris, they consider me blessed. Paris is the most romantic city in the world, after all, with its bridges where lovers have kissed for centuries; it is the heart of fashion, elegance and art. But there is another side to Paris that the world does not know so well. So this month in my round-the-world journey for Glamour, I have chosen to write from the city where I live, but about a part of it that only people like Fatima know.

Fatima is among the thousands of Moroccan, Algerian and Tunisian immigrants who came to Paris in the eighties and ended up in low-paying jobs. They lived in flats that Parisians refer to as chicken cages—rows of concrete buildings reminiscent of subsidized housing projects in America. I spent a lot of time in these French neighborhoods in my early years as a reporter, and I met many immigrants who felt inadequate and powerless. Once, I sat with a man named Mustapha as he replied to a job ad. To prove a point, he called twice, first using a French name and then his own name. With the French name, he got an interview; with his own name, he was told the job had been filled. When he hung up the phone, his hand was shaking. This was what injustice felt like, and it is this kind of frustration, rooted in race, religion and identity, that in 2005 drove the kids of immigrants to set hundreds of cars on fire in riots around Paris, and to torch buses this fall in another display of fury.

Fatima’s life story is typical of Arab women of her generation. In her book, she tells of her life as a girl in Morocco. When she was 12, she left school because her parents could afford to educate only her two brothers. So she set aside her girlhood dreams of studying literature and instead lived at home, helping her 11 sisters learn to read, sew and cook. Eventually she wed a man who brought her to France and fathered two girls; later he and Fatima separated. To feed her kids, Fatima cleaned as many as five homes a day, getting up at 4:00 in the morning, scouring floors, losing her self-esteem and, she says, “forgetting my own femininity.”

In Prière, Fatima describes the difficulties of trying to integrate with French society while also maintaining her Arab heritage. She tells how she tried to help her daughters navigate the two worlds, but as they neared adolescence, they grew increasingly distant, even hostile. Fatima’s anguish peaked when one of her girls asked for help with her schoolwork. “Do you know how it feels to have your child crying because her mother can’t read and write in French?” Fatima asks. She knew she couldn’t learn French fast enough to help her child, but she could give her something else. “I understood my daughters needed something bigger than me. It wasn’t clothes, food or love. It was knowledge. It was culture.” So she sat by the window and began to write, using the Arabic she’d learned at school. She “wrote to the moon,” she says, her silent companion, the sole witness to her life as a woman with a past, a religion and a soul. Her style was poetic: “We have discovered the secrets of the earth,” she wrote. “We have found wealth at the bottom of the ocean and fetched stones on the moon, but we can’t see the treasures we have at arm’s length.”

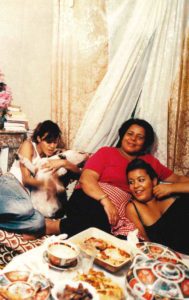

As Fatima and I talk, her daughter Sokaina, a pretty, plump 18-year-old, bursts through the door. She is followed by her sister, Mariam, 21, who arrives wearing a T-shirt and sexy white shorts. The radio is playing Arabic songs, and the flat smells of couscous, the traditional Moroccan dish. Mariam has brought her “two babies,” a pair of bulldogs that frantically search the place for interesting new odors. I glance out the window and wonder if it is even possible to see the moon in such a restricted urban landscape.

The girls gather near us while Fatima continues telling her odyssey. She says she kept on cleaning and writing, but one day she collapsed from exhaustion. Afterward, she could barely find the mental or physical strength to get out of bed. So she sought help from a psychiatrist. “This was the first time I shared my life with anyone,” Fatima says. She talked about her writing, and the therapist helped her find someone who could translate her story into French for free. Reenergized, Fatima visited a book fair and introduced herself to elite editors, who expect their writers to have years of education. Remarkably, a publisher called soon after.

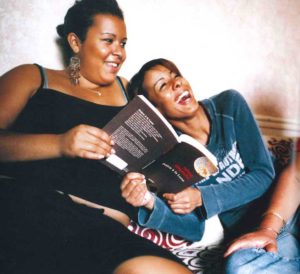

As Fatima gets up to attend to the couscous, I chat with Sokaina, a high school student, and Mariam, who’s now between jobs but tells me she used to make good money working in a bar at night. They remind me of the Muslim friends I had at their age and how they struggled. Being a good Muslim and a typical French girl meant bridging an impossible divide. At school you had to be hot; you had to wear makeup and drink at parties, but at home this behavior was considered a sin. Things have only gotten worse since then: Increasingly girls who flout traditional Muslim notions of modesty are being attacked by youth gangs; one woman was even burned to death in 2002. “I don’t know who I am,” Mariam says. “I am both a die-hard party girl and a deeply religious person. Sometimes I am one, sometimes the other, but I can never be both.” As Mariam confides in me, she looks fragile. She is constantly laughing, as if to downplay her struggle. “When you’re Arab, everyone judges you,” she says. “The worst comes from within the community.”

Like Mariam and Sokaina, I grew up as an immigrant in Paris. But my ethnicity—Cuban and Dutch—was deemed exotic, and I never felt discriminated against, unlike the kids whose parents came from North Africa. My mother single-handedly raised my brother and me, and we barely made ends meet, but I was lucky: I lived inside the city and not in its grim suburbs. And, in another profound difference between other immigrant kids and me, I was utterly proud of my mother. My friends rarely mentioned their parents. Their moms and dads, with their unglamorous jobs and foreign values, were a matter of discomfort or shame. There are immigrants I’ve known for decades who have never told me what their parents did for a living—let alone how they felt.

That is why I know how courageous it is for Fatima to share her life and put a face on all the invisible immigrant mothers. Ever since her book was published in the fall, she has been all over the French media. Professors are discussing how astounding it is to hear an authentic voice of a long-silent community. The people in the homes Fatima once cleaned are suddenly taking notice of the great distances their workers travel to their jobs. Says Fatima, “We know French people. We go to their homes and clean their dirt. But until now, the French didn’t find it necessary to discover who we immigrants are as people.” Fatima no longer cleans homes and is writing another book, also autobiographical.

In the flat’s only bedroom, I hear Fatima’s girls giggling and arguing gently over clothes. “Shhh,” says Fatima, turning on the radio. She’s about to be featured on a popular news program. As the segment starts, everyone falls silent, listening to the unlikely voice of Fatima, the cleaning lady.

Once the show is over, the girls tell me they didn’t really understand that their mom was writing a book until it was finished. “I would come home at 3:00 in the morning and see her bent over the dining room table with her big glasses, crossing out words and rewriting them,” Sokaina says. She waves a copy of Closer, a French tabloid, and turns to a page featuring her mom. “You know what is probably the most beautiful moment of my life?” Sokaina asks. “It was not so long ago, when I was filling out papers for my school. In the ‘mother’s profession’ box, instead of putting the usual ‘cleaning lady,’ I got to say ‘writer.’”

Archive

Dear 20 seconds-average attention span user

I am writing to say that I am hereby joining …

CHIME Through the Years: North America

Featuring the stories of women and girls across North America …